Relevancy and Engagement

massachusetts.agclassroom.org

Relevancy and Engagement

massachusetts.agclassroom.org

Food: Going the Distance

Grade Level

Purpose

Students calculate the miles common food items travel from the farm to their plates and discuss the environmental, social, and economic pros and cons of eating local vs relying on a global marketplace for our food. Grades 9-12

Estimated Time

Materials Needed

Engage:

- Food: Going the Distance, 1 copy per class

Activity 1: The Environmental Footprint of Food Miles

- Why You Should Know Where Your Food Comes From video

- You want to reduce the carbon footprint of your food? Focus on what you eat, not whether your food is local article

Activity 2: The Social and Economic Impact of Food Miles

Vocabulary

commodity: a primary agricultural product that can be bought and sold

consumer: a person who buys and uses goods and services

distribution: the action or process of supplying goods to stores and other businesses that sell to consumers

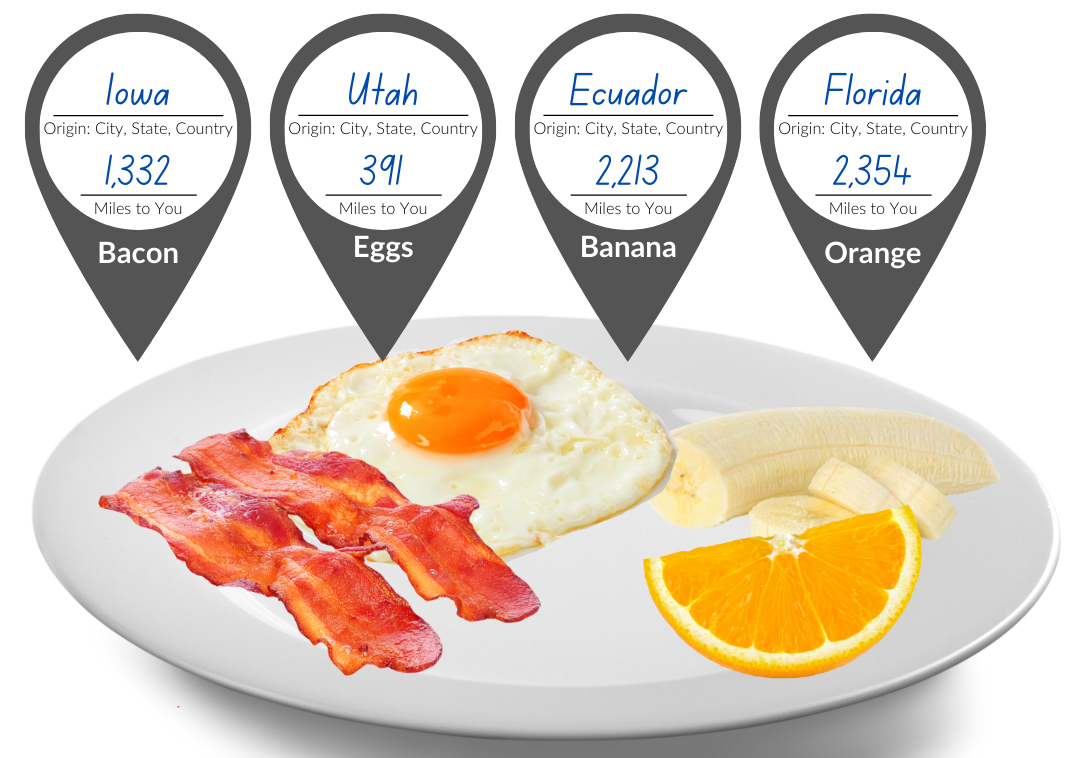

food miles: the distance food is transported from the time of its production until it reaches the consumer

food processing: the process of transforming raw agricultural products, like grains, vegetables, meat, or milk, into end products to be sold to consumers

locavore: a person whose diet consists only or principally of locally grown or produced food

supply chain: the sequence of processes involved in the production and distribution of a commodity

Did You Know?

- It is estimated that meals in the United States travel an average of 1,500 miles to get from farm to plate.1

- Food travels by plane, train, truck and even cargo ship. Each mode of transportation uses fossil fuels and emits carbon dioxide.1

- Food transportation by plane has the highest carbon footprint. Planes emit more carbon dioxide than trains, trucks, or cargo ships.2

Background Agricultural Connections

How does food get to the grocery store? The term supply chain is used to describe the sequence of processes involved in the production, processing, and distribution of a commodity. The chain begins with the equipment farmers need to produce food, such as seeds, fertilizer, and machines. Farmers then plant, maintain, and harvest crops or raise animals. The food is cleaned, processed, and packaged before being shipped to grocery stores and into the hands of consumers.

Transportation is a critical part of the supply chain. Transportation is required to link each step in the chain. Today we live in a global marketplace for food. In 2016 it was estimated that 82.6% of the food in America was produced domestically.3 The remaining percentage of food is imported from other countries. Why would we import food? Most varieties of produce, including berries with specific seasons and growing specifications can now be purchased year-round in most grocery stores in the United States. Gone are the days that specific foods are only available in specific weeks or months of the year. Distributors source foods from different areas throughout the world according to season and availability. For example, when strawberries aren't available from farms in California or Florida, they may be available from parts of Latin America.

Some regions cannot produce certain foods due to population density (lack of farm land), seasons, and climate and soil conditions. Consumers living in these regions rely on farms in other geographic areas to produce their food supply. In the United States, food is shipped an average of 1,500 miles before being sold to the consumer.1 The five main modes of transporting agricultural products are trucks, trains, airplanes, and cargo ships.

The concept of food miles was introduced in the 1990s to describe the number of miles a food traveled on its journey from farm-to-plate. The use of food miles is often tied to locavore movements which emphasize the consumption of locally-grown foods.

The Environmental Impact of Food Miles

Food miles contribute to the overall carbon emissions of our food. Trucks, trains, planes, and cargo ships all require fossil fuels to move our food from the producer (farmer) to the consumer. It seems logical that lowering our food miles would result in lowering the overall environmental footprint of our food. However, the comparisons are not this clear or simplistic. Not all food miles are created equal. The type of transportation used to transport food impacts carbon emissions more than the food miles themselves. Transporting food by air emits about 50 times as much greenhouse gas as transporting the same amount of food by sea.4 The majority (58.97%) of global food miles come from transport by sea, followed by the road, railways, and air representing only a fraction.4 See more details on the Share of Global Food Miles by Transport Method chart.

If you look at the entire farm-to-fork supply chain, the area where the greatest improvements can be made to reduce carbon emissions is in production practices. For example, growing tomatoes in a greenhouse and shipping them a short distance to a local market may have a deeper environmental footprint than growing tomatoes in a naturally warmer climate and shipping the tomatoes a longer distance due to the energy requirement of the greenhouse. Careful evaluations should be made from a wide scope rather than a sole focus on food miles.

The Economic Impact of Food Miles

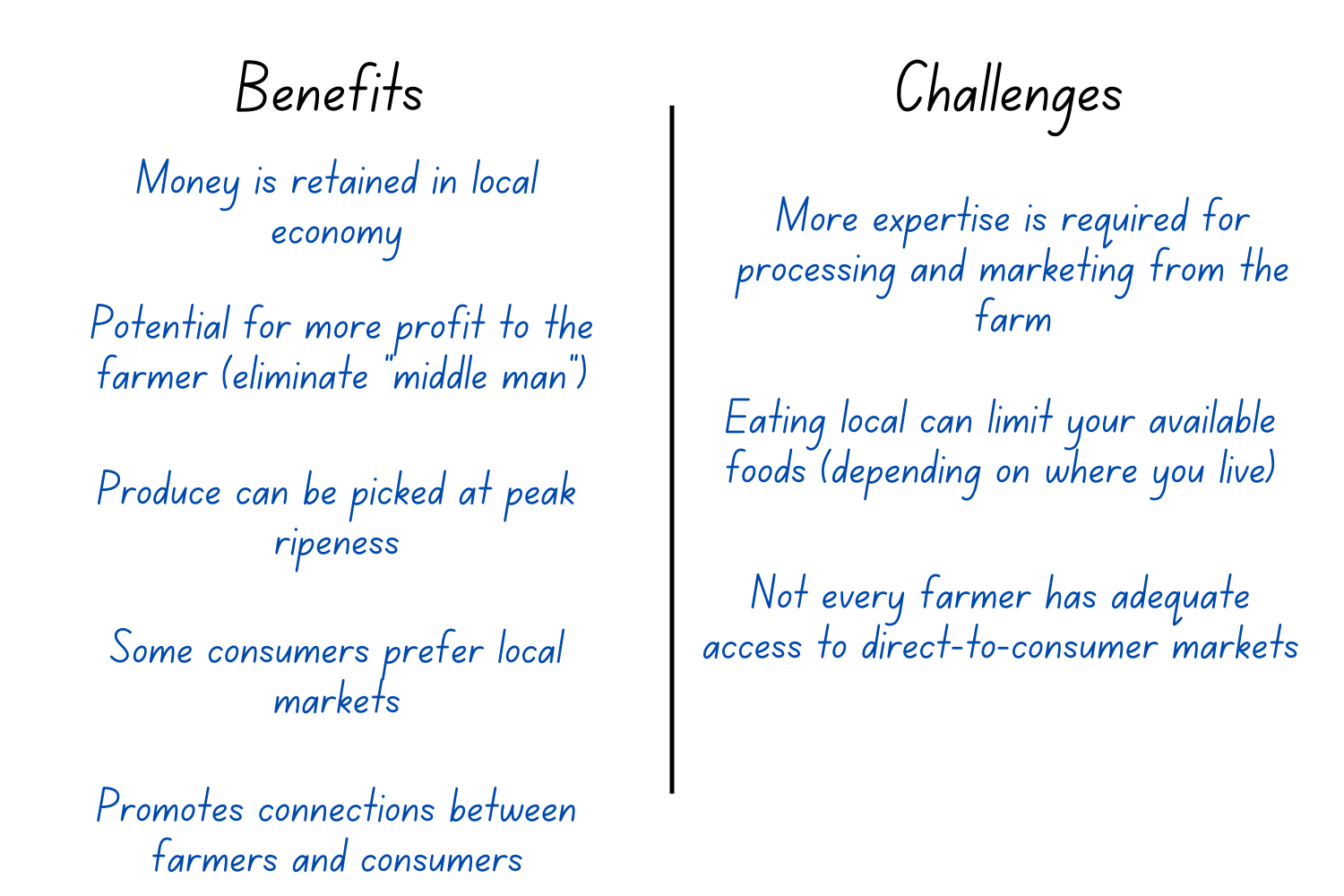

Every farmer must choose a market for their commodity that can provide economic stability. Farmers face many risks and challenges. Price fluctations, varying crop yields, challenging weather conditions, and rising production costs are a few. The market they choose will influence their economic sustainability and the food miles that will be associated with their product. Some farm commodities can be sold locally to consumers through farmer's markets, Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), or other direct-to-consumer (DTC) sales. Other times commodities are sold to processors or other wholesale markets where the raw farm product is processed, packaged, or stored before it is ultimately sold to a consumer.

The Economic Research Service (ERS) found that farmers who market goods directly to consumers are more likely to remain in business than those who market only through traditional channels.6 DTC marketing can eliminate steps in the food supply chain, leading to the potential of a greater return to the producer. However, it also requires a wider spectrum of skills to market the product. When dollars are spent locally, they can be re-spent locally as well.7

The Social Impacts of Food Miles

Local food supports local cultural identity. Food and culture have a deep connection that includes where the food was grown or produced. Eating locally grown food also helps promote food security because the availability of imported food can be dependent on outside influences like sociopolitical conflicts which can disrupt the food supply chain.

There are also social challenges that arise with food miles. The production of food in developing countries to export to developed countries can lead to inequity and greater likelihood for malnutrition when large-scale food transport encourages export rather than using their food for self-sustaining.5 The social gap widens as the environmental burden of food production (soil degradation, water depletion, etc.) leaves developing nations with even fewer resources to provide for themselves.

Engage

- Prior to class, give each student (or teams of students) one page from the Food: Going the Distance PDF to complete as homework. Instruct students to visit the grocery store before the next class period and follow the instructions on the handout to discover where each food item was produced and the miles the food traveled to arrive at your local grocery store.

- Offer the following tips:

- All produce must be marked with a country of origin if it is grown outside of the United States. Study the labels or stickers to find the origin.

- Produce that was grown in the United States often has a farm address or other indication of its source.

- All meat in the United States is required to be labeled with the country of origin. Some meats may be more difficult to find the origin, especially if it is a store brand (ie: Food Club, Great Value, etc.) Meats with specialty labels such as grass-fed, USDA organic, etc. are more likely to indicate the farm origin. If students don't find the information on the first package they find, they should explore other brands.

- If students have tried multiple packages or brands and still cannot find an origin, allow them to make a substitution using a food that is comparable in nutritional value.

- Remind students that they are looking for the farm where the food was produced, not the distributor.

- As students arrive in class, ask them to place their Food: Going the Distance sheet on the board with a magnet or tape. Allow students to share what they learned about the origin of their assigned foods along with the tally for total food miles.

- Project the Eat Local sign collage on the board. Ask students if they have ever seen a similar sign or message.

- Ask students, "Why would eating local be advertised or thought of as as a better choice?" Allow students to share their ideas.

Explore and Explain

Activity 1: The Environmental Footprint of Food Miles

- Introduce the concept of food miles by watching Why You Should Know Where Your Food Comes From. Stop the video at 6:53.

- Following the video, discuss the following questions:

- What is a "food mile?" (a mile over which a food item is transported during the journey from producer to consumer)

- What transportation methods are used to move food through the supply chain? (planes, trucks, rail, or cargo ship)

- Does fewer food miles always equate to an overall lower carbon footprint? (No)

- Read, You want to reduce the carbon footprint of your food? Focus on what you eat, not whether your food is local. Assign the reading to individual students, groups, or review the article as a class. Project the Food: greenhouse gas emissions across the supply chain chart to illustrate greenhouse gas emissions across the supply chain. Note that the chart is interactive, and you can select specific foods you would like to evaluate.

Teach with ClarityThe article used in Step 3 is from Our World in Data. The author uses global averages for the charts and data. Animal agriculture in the United States typically has a smaller percentage of total GHG emissions than global averages due to production efficiencies and technology available here.8 For example, in Mexico, it takes up to five cows to produce the same amount of milk as one U.S. cow. In India it may take up to 20 cows. While the exact GHG emission numbers may be different in the United States, the take-home message for this learning activity is that food miles contribute to greenhouse gases, but in much smaller proportions than other activities in the food supply chain. |

Activity 2: The Social and Economic Impact of Food Miles

- Explore the social and economic impact of food miles using one of the activities below:

- Option 1: Guest Speaker. Find a local restaurant or retail store that specializes in selling their own farm-to-fork food or locally produced food. Invite the owner to be a guest speaker in your class. Invite them to share their business and explain the benefits and challenges to their business model. Use the LocalHarvest webpage to search by zip code or find local advertisements.

- Option 2: Assign student groups to find a local restaurant or retail store that specializes in selling their own farm-to-fork food or locally produced food. They should visit the farm/store and ask if they could visit with the owner or a manager to learn more about their business. Use the Food Miles: Direct-to-Consumer Sales Questionaire as a guide to their discussion. Invite students to share with the class what they learned.

- Summarize with students some of the benefits and challenges farmers experience when they market their products directly to consumers. Keep a list on the board. Use examples below to help promote class discussion. Additional discussion points can be found in the Background Agricultural Connections section of this lesson plan.

Elaborate

- Dig deeper into understanding why specific foods are grown in specific geographic regions using the lesson, Geography and Climate for Agricultural Landscapes.

- Explore your state's program that promotes local foods.

- Buy Alabama's Best

- Alaska Grown

- Arizona Grown

- Arkansas Grown

- CA (California) Grown

- Colorado Proud

- CT (Connecticut) Grown

- Delaware Grown

- Fresh From Florida

- Georgia Grown

- Hawai'i Seals of Quality

- Idaho Preferred

- Illinois Buy Fresh Buy Local

- Indiana Grown

- Choose Iowa

- From the Land of Kansas

- Kentucky Proud

- Louisiana Grown. Real. Fresh.

- Get Real. Get Maine.

- Maryland's Best

- Massachusetts Grown...and Fresher!

- Pure Michigan

- Minnesota Grown

- Genuine MS (Mississippi) Grown

- AgriMissouri

- Made in Montana

- Buy Fresh Buy Local Nebraska

- Made in Nevada

- New Hampshire Made

- (New Jersey) Jersey Fresh

- (New Mexico) Taste the Tradition

- New York State Grown and Certified

- Got to Be NC (North Carolina)

- Pride of North Dakota

- Ohio Proud

- Made in Oklahoma

- Buy Oregon Agriculture

- PA (Pennsylvania) Preferred

- Get Fresh Buy Local (Rhode Island)

- Certified South Carolina Grown

- South Dakota Local Foods Directory

- Pick Tennessee Products

- Go Texan

- Utah's Own

- Dig in Vermont

- Virginia Grown and Virginia's Finest

- Washington Grown

- West Virginia Grown

- Something Special from Wisconsin

- Grown in Wyoming

- Ask students to read Direct Marketing from the UC Davis Sustainable Agriculture Research Education Program.

- Take a deeper dive into the food supply chain using the lesson, Tracing the Agricultural Supply Chain.

Evaluate

After conducting these activities, review and summarize the following key points:

- Food is grown all over the world in areas with adequate space, natural resources (water, arable soil, etc), and climate. After food is produced on the farm, it is shipped by truck, plane, train, or cargo ship to reach consumers.

- Transportation, commonly known as "food miles" accounts for 5% of food's greenhouse gas emissions. Eating local foods does not contribute to a significant decrease in food's environmental impact, but it does have social and economic benefits.

- Local-food movements can impact patterns of food production and consumption.

- Urbanization is one factor that contributes to the need to transport food longer distances. As cities grow, the production of food takes place on larger farms located farther from cities.

- When considering sustainability, environmental, social, and economic factors should be considered.

Sources

- How Far Does Your Food Travel to Get to Your Plate? | Foodwise

- The Facts About Food Miles | BBC Good Food

- Kay's Korner: The Food Waste Scandal | Western Livestock Journal

- Very Little of Global Food is Transported by Air | Our World in Data

- Food Miles | Sustainability: A Comprehensive Foundation

- Farms that Sell Directly to Consumers May Stay in Business Longer | USDA

- Why Buy Local? | Center for Community and Economic Development

- It's Time to Stop Comparing Meat Emissions to Flying | GHGGuru Blog